In a recent two-part webinar series (Click here for part one and here for part two), The Vera Institute of Justice (Vera) profiled three jurisdictions using various strategies to implement PREA’s “youthful inmate” standard:

- Oregon: Scott Taylor and Craig Bachman, from the Multnomah County Department of Community Justice, described the county’s policy of housing youthful inmates in juvenile facilities. Philip Cox, from the Oregon Youth Authority, also spoke about Oregon’s policy of keeping youthful inmates in juvenile facilities until the age of 25.

- North Carolina: Warden Bianca Harris, from the North Carolina Correctional Institution for Women, explained her facility’s creation of a separate housing unit for female youthful offenders.

- Indiana: Michael Dempsey and James Basinger, from the Department of Corrections, outlined Indiana’s recent legislative changes, which enable youth sentenced as adults to be committed to a juvenile facility, and described Indiana’s approach to youth not covered by the new laws.

“Youthful Inmate” Standard

PREA Standard § 115.14 on “youthful inmates” says that any person under the age of 18, and incarcerated or detained in a prison or jail, must be housed separately from any adult inmates and, outside the housing unit, “sight and sound separation” or direct staff supervision must be maintained. Agencies must use best efforts to avoid using isolation to comply with these conditions, and must afford youthful inmates the opportunity for daily large-muscle exercise, and to take part in special education services, programs and work opportunities, absent exigent circumstances. This standard demands significant resources, so agencies are afforded flexibility in finding a way to comply.

It is worth noting that, where state law requires the automatic prosecution in adult court of youth at age 16 as it does in North Carolina, the state still must comply with the youthful inmate standard.

Options for Implementation

PREA standards can be met by housing youth convicted as adults in juvenile facilities. Housing youth outside the adult correctional system meets the developmental needs of the youth population and improves access to developmentally appropriate services. Where it is not possible to house youthful inmates in a separate facility, they may be housed in a separate wing of an adult facility, or transferred to another facility which has such a wing available. Below you can find more information about how some jurisdictions are implementing this standard including links to sample policies and bills.

- Reducing the number of youthful inmates in adult facilities as a matter of policy or law

A number of agencies are seeing the benefits of housing youthful inmates in juvenile facilities. Oregon and Indiana institutionalized the practice through legislation.

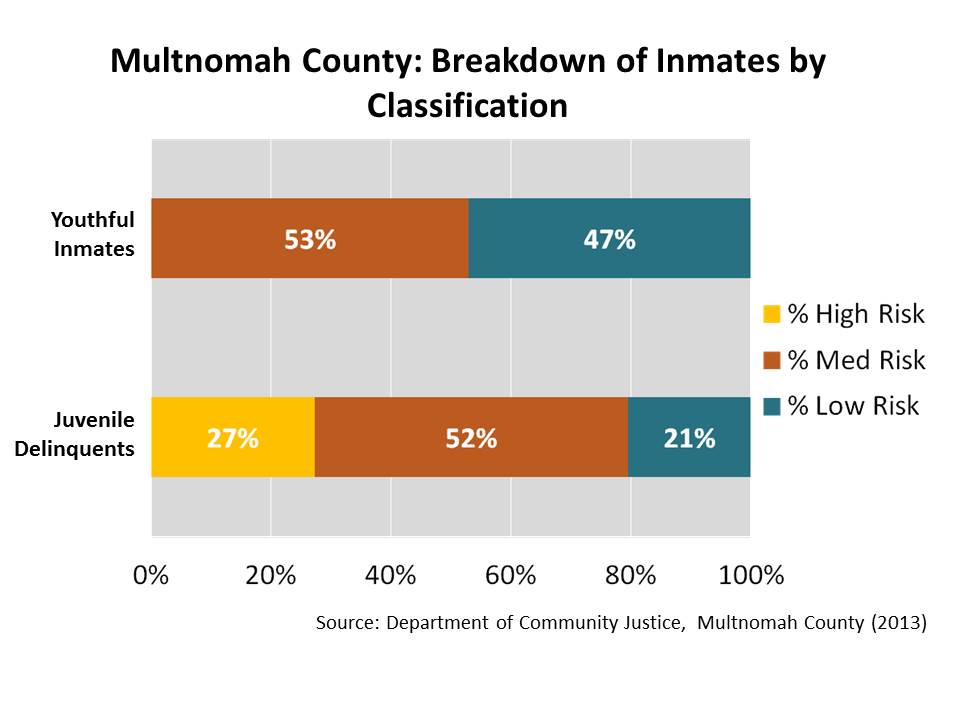

Multnomah County, Oregon passed a county resolution, establishing a presumptive rule that all juveniles in county custody be housed in juvenile detention. Juveniles are frequently tried as adults in Oregon, due to the state’s expansive legislative waiver provisions. Under the resolution, which codified existing county practice, youthful inmates are housed in juvenile detention unless the sheriff and corrections commissioner agree to alternative placement. Relocation to an adult facility is governed by a transfer agreement, which permits transfer only when the youth exhibits escalating behavior that poses a safety risk to staff and other youth and fails to engage with programming and behavioral interventions.

In the case of Oregon state prisons, legislation passed in 1995 allows for youth under the age of 18 who are tried and convicted as adults, for offenses committed as minors, to serve out their time in juvenile correctional facility. Youth can be transferred to a state juvenile correctional facility if their sentence will be completed before they turn 25, or if it would be more appropriate to house them there initially, due to their age, immaturity, mental or emotional condition, or risk of physical harm. They can remain in the facility until the age of 25, provided they participate in programming and follow facility rules.

In Indiana, House Bill 1108, signed into law on April 29, 2013, provides judges with an additional sentencing option for juveniles who are tried as adults. The legislation was passed following collaboration between the Department of Corrections, the Division of Youth Services, juvenile judges, prosecutors, public defenders and legislators. Judges may, with the consent of the prosecutor, suspend the adult sentence imposed on a youthful offender and order instead that the youth be placed in a juvenile facility. Successful completion of the stay in juvenile facility is a condition of suspension. When the youth turns 18 year of age, a progress report is prepared and a review hearing conducted, at which time the court may order that the youth remain in the juvenile facility, move to an adult facility, move to a non-custodial sentence, or undergo a complete discharge (if the objectives of the original sentence have been met). Under this model, Indiana’s legislature permits youth convicted of adult crimes to be housed in juvenile correctional facilities without modifying the waiver provisions.

- Entering into a cooperative agreement with an outside jurisdiction to facilitate compliance

Youthful inmates can also be housed in juvenile facilities under an agreement with youth facilities. In Indiana, all youth sentenced to imprisonment as adults are interviewed and assessed on intake. If appropriate, a recommendation is made to the Commissioner of Corrections that a youth be housed in a juvenile facility, where they receive juvenile programming and services, and can remain until the age of 18.

- Confining all youthful inmates to a separate housing unit Implementation of the youthful inmate standard can also be accomplished through separate housing within an adult facility. North Carolina’s Correctional Institution for Women houses its small population of youthful inmates in a separate wing of the facility, which was created by renovating a wing of a building on the campus. Inside the new wing, administrators provide separate classrooms, library, recreational opportunities, social work and counseling services, and dining space. Because youthful inmates have to travel to reach the medical center, there is a “chaperone” system in place to lead youth to the medical center and accompany them while they are there. Privacy is ensured in the medical center by placing magnetic cloth coverings over windows during examinations; this also prohibits youthful inmates from seeing adults when in the medical building.

Lessons Learned

Keeping youthful inmates out of adult facilities makes operational sense. First, where youth occupy only a fraction of the available beds in a particular housing unit, implementing PREA renders the remaining beds unusable. Second, juvenile facilities are set up, and the staff properly trained, to respond to the unique needs and challenges of youth. Adult facilities, by contrast, typically lack such specialists, and their staff may require additional training before they can effectively serve youth. Some youth require especially intense supervision and care, and this places great strain on staff involved in service delivery. Finally, there are no mistakes or confusion among law enforcement and other agencies when determining where to place an individual under the age of 18 who is tried as an adult.

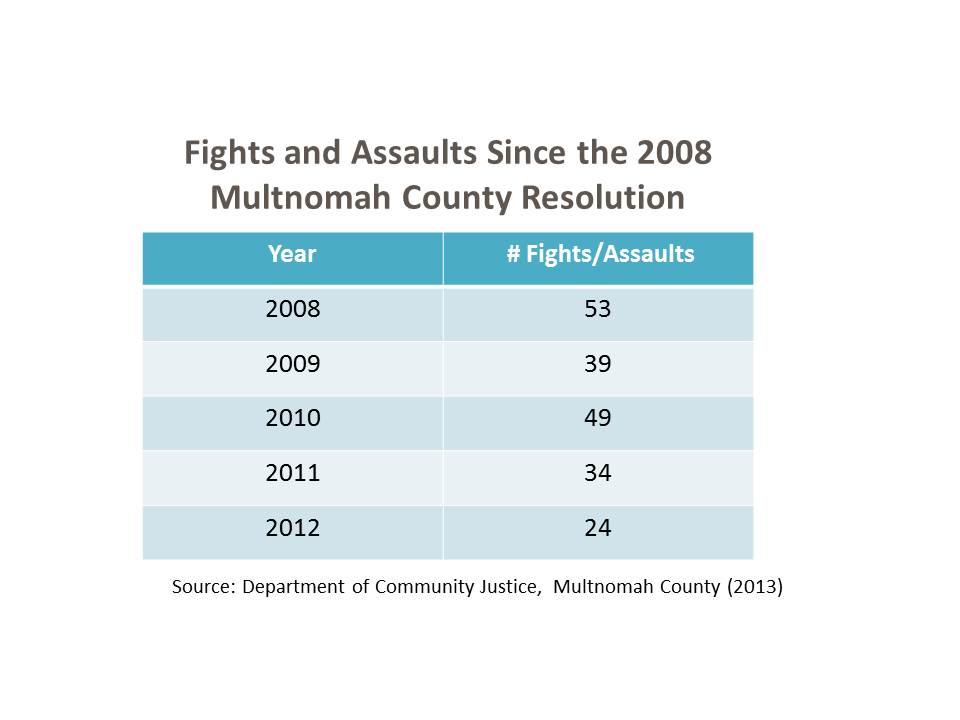

Housing youthful inmates in juvenile facilities can be achieved without disruption. Since youth convicted of adult crimes have been housed in Oregon’s juvenile detention facilities, the number of fights has decreased, not increased as some staff had feared. Similarly, in Indiana, although the process has been in place for only a short time, youth who have been transferred to the juvenile system fit in with the other juveniles at the facility, and are yet to be involved in any serious incidents.

Correctional facilities will face additional challenges if they only supervise a small population of youthful inmates. North Carolina’s Institution for Women houses, on average, only five youthful inmates. Because it is difficult to convene recreational activities with such a small group, prison authorities are considering how to further involve staff and volunteers, and what other activities might be arranged. In addition, the youth have often already met their educational requirement, so alternative academic pathways are being explored for them. Job opportunities also present a challenge: the youth cannot work together with adult inmates, but it is difficult to identify alternative income-earning opportunities for them.

For Indiana, the key to attracting support for legislation to house youthful inmates in juvenile correctional facilities was to help legislators understand that this change is not about being “soft on crime,” but about ensuring kids are receiving the right services in the right place. It was helpful to make available data showing that public safety is improved if youthful inmates have access to appropriate services. Finally, the support of the prosecutors was crucial. Likewise, obtaining buy-in from staff was achieved by ensuring that they, too, understood the real reasons for the change, and that it was easier for them if children are paired with staff who are trained to deal with their particular needs.

Resources

Implementing the Youthful Inmate Standard Part 1: Lessons from the County and State Level in Oregon

Implementing the Youthful Inmate Standard Part II: Spotlight on Indiana and North Carolina

PREA Standards for Prisons and Jails – click “§ 115.14 Youthful inmates” for youthful inmate standard

FAQ on Youthful Inmate Standard

PREA Essentials

Multnomah County, Oregon County Resolution

Oregon Transfer Agreement

Indiana House Bill 1108